"I think the Battle of Versailles captured the sense of transformation that was such a part of the 1970s. Each of the American designers, in their own way, reflected change. Anne Klein captured the new feminism. Halston was part of the rise of celebrity culture. Bill Blass and Oscar de la Renta both were examples of the distance that American designers and the American fashion industry had come. Stephen Burrows spoke to the social liberation. And certainly the black models—and their impact on the show and influence on the other models—captured the tumultuous racial climate."- Robin Givhan, author of The Battle of Versailles."

"By the early ’70s, she was making 15-foot-tall “very hairy

and fetishy” charcoal hybrids of penises and screws, a play on “screwing,” as

in fornication, and “getting screwed,” as in being mistreated. “The idea is

funny, but the execution was very raw,” she says. “They were very warlike and

missilelike and ominous.”

"If you read anything about Susan Sontag written since

her death in 2004, it won’t take long for you to stumble across the fact that

she could be, as Terry Castle puts it in her agonizingly generous essay

"Desperately Seeking Susan," "weally weally mean!" Sontag’s arrogance, her

condescension, her inhospitality — often, the earlier and more prominently

these ad feminam excoriations figure in the review at hand, the less earnest

the engagement with her work that follows. (One can’t help but notice that the niceness

of her male peers is rarely considered so central to their legacy; the press

hath no scorn like for a woman-fury.) Eventually, this preoccupation becomes

more than a distraction — it becomes a crutch to excuse shallow inquiry into

her work. That is not the problem with Daniel Schreiber’s Susan Sontag, first

published in German and translated by David Dollenmayer, the first biography

published since her death. It offers an opportunity to reassess how we approach

the last great public intellectual."

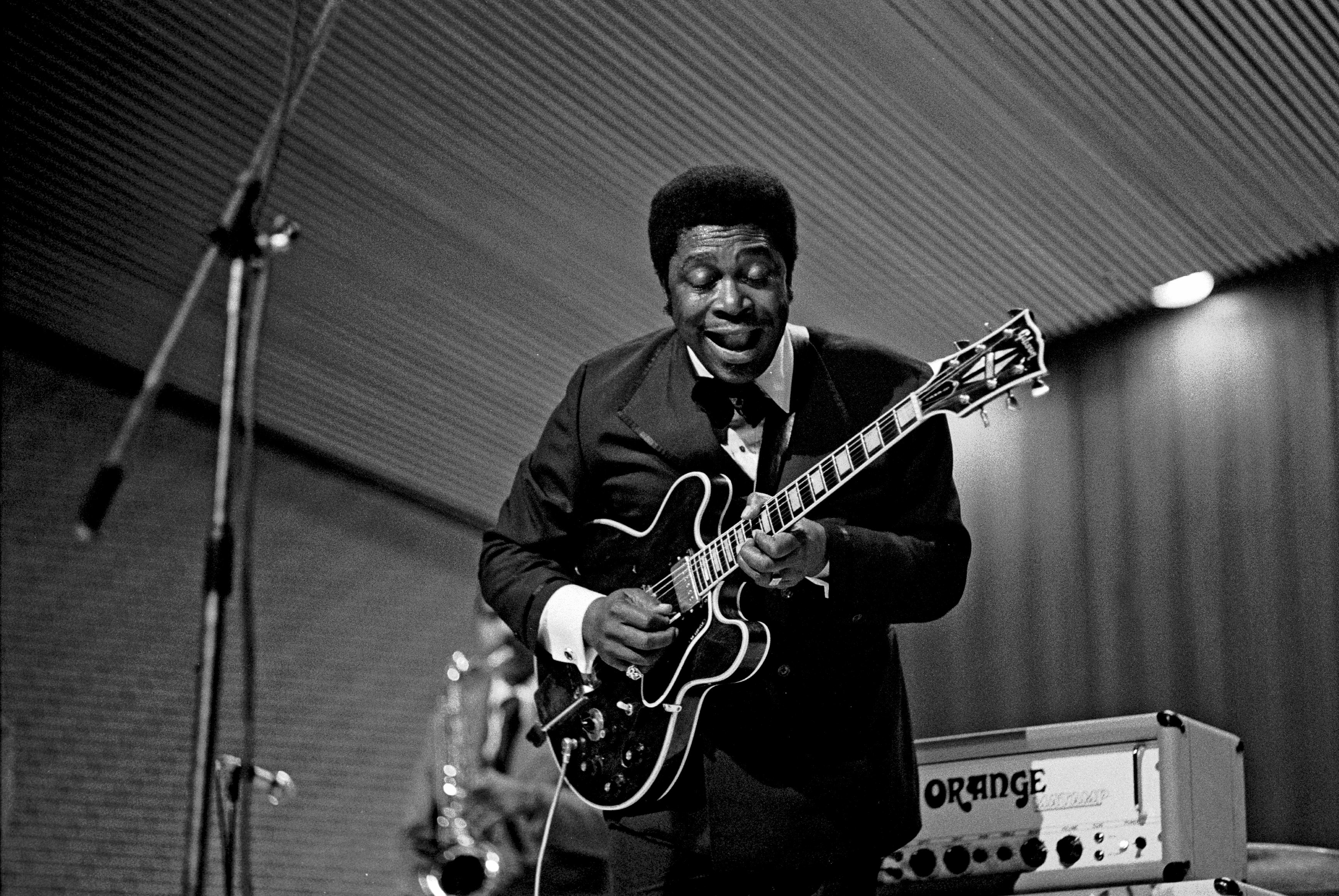

"With the release "The Thrill is Gone"

(1969), B.B. King solidified his role as Black music's ambassador to the world.

Throughout the 1970s King also found crossover success with singles like

"Ain't Nobody Home" (1972) and "To Know You Is To Love You"

(1973), which was written and originally recorded by Stevie Wonderand Syretta

Wright; Wonder appears on the King version, effectively capturing two

generations of black music listeners, at a moment when Wonder was ascending to

his own iconic status. By the time King released 1974's Friends, with the title

track and the instrumental "Philadelphia," which sounds like the best

of what was produced at Sigma Sound Studios in that era, the mainstream pop

audiences were gone, looking more for nostalgia from the Claptons and Steve

Millers of the world than forward thinking from "old" Blues musicians."

“We’re constantly being bombarded with the same image of

black people, over and over again—the same tropes played out again and again in

media and in movies and in journalism and popular culture. So to see something

that is contrary to the dominant narrative is so refreshing,” says Shantrelle

P. Lewis, the curator of “Dandy Lion” who began documenting the black dandy in

2010. “When [black men] walk inside this exhibition, they see themselves

reflected on the wall, and it’s a very powerful thing.”

"Librarians have frequently been involved in the fight against government surveillance. The first librarian to be locked up for defending privacy and intellectual freedom was Zoia Horn, who spent three week in jail in 1972 for refusing to testify against anti–Vietnam War activists. During the Cold War, librarians exposed the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s attempts to recruit library staffers to spy on foreigners, particularly Soviets, through a national effort called the Library Awareness Program."